In 1960 the laser, one of the most important and versatile scientific instruments of all time, was invented. It was on 16 May 1960, that the North American physicist and engineer, Theodore Maiman (1927-2007), obtained the first laser emission.

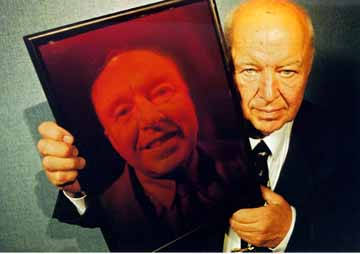

Theodore Maiman (1927-2007), winner of the Wolf Foundation Prize in Physics, 1983 Credit: AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives.

This date is therefore of great importance not only for those of us who carry out research in the field of optics and other scientific fields, but also for the general public who use laser devices in their daily lives. CD, DVD and Blu-ray players, laser printers, barcode readers, and fibre-optic communication systems that connect to the worldwide web and Internet are just a few of the many examples of laser applications in our daily life. Lasers also have a range of important biomedical applications; for example they are used to correct myopia, treat certain tumours and even whiten teeth, not to mention the beauty clinics that continually bombard us with advertisements for laser depilation, which has become so popular nowadays. However, the laser is of great importance not only due to its numerous scientific and commercial applications or the fact that it is the essential tool in various state-of-the-art technologies but also because it was a key factor in the boom experienced by optics in the second half of the last century. Around 1950 optics was considered by many to be a scientific discipline with a great past but not much of a future. At that time, the most prestigious journals were full of scientific papers from other branches of physics. However, this situation changed dramatically thanks to the laser which led to a vigorous development of optics. It is indisputable that the laser triggered a spectacular reactivation in numerous areas of optics and gave rise to others such as optoelectronics, non-linear optics or optical communications.

This date is therefore of great importance not only for those of us who carry out research in the field of optics and other scientific fields, but also for the general public who use laser devices in their daily lives. CD, DVD and Blu-ray players, laser printers, barcode readers, and fibre-optic communication systems that connect to the worldwide web and Internet are just a few of the many examples of laser applications in our daily life. Lasers also have a range of important biomedical applications; for example they are used to correct myopia, treat certain tumors and even whiten teeth, not to mention the beauty clinics that continually bombard us with advertisements for laser depilation, which has become so popular nowadays. However, the laser is of great importance not only due to its numerous scientific and commercial applications or the fact that it is the essential tool in various state-of-the-art technologies but also because it was a key factor in the boom experienced by optics in the second half of the last century. Around 1950 optics was considered by many to be a scientific discipline with a great past but not much of a future. At that time, the most prestigious journals were full of scientific papers from other branches of physics. However, this situation changed dramatically thanks to the laser which led to a vigorous development of optics. It is indisputable that the laser triggered a spectacular reactivation in numerous areas of optics and gave rise to others such as optoelectronics, non-linear optics or optical communications.

What is a laser?

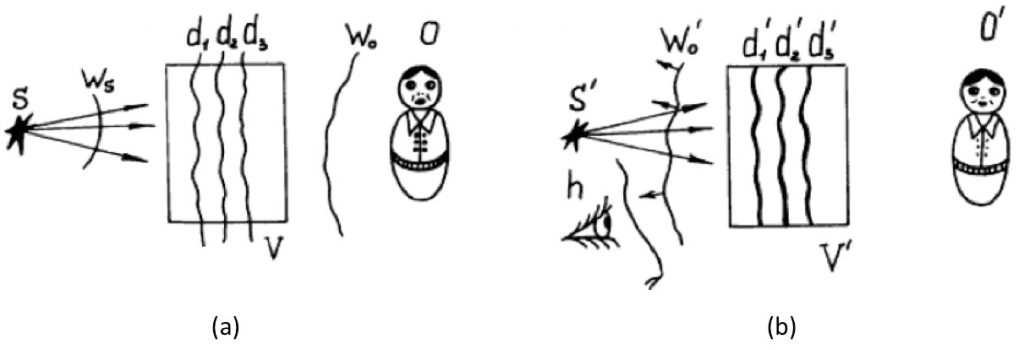

It is a device capable of generating a light beam of a much greater intensity than that emitted by any other type of light source. Moreover it has the property of coherence, which ordinary light beams usually lack. The angular dispersion of a laser beam is also much smaller and so when a laser ray is emitted and dispersed by the surrounding dust particles it is seen as a narrow straight light beam. But let us leave to one side the specialized technical points, more suitable to other types of publications, and concentrate on aspects of the invention of the laser which are no less important and no doubt of greater interest to the general public. The word laser is actually an acronym for “Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation” and was coined in 1957 by the American physicist Gordon Gould (1920-2005), working for the private company Technical Research Group (TGR), who changed the “M” of Maser for the “L” of Laser. In the image below, the phrase “some rough calculations on the feasibility of a LASER: Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation” may be seen (Gordon Gould’s manuscript, 1957).

First page of Gordon Gould’s 1957 lab notebook where he defines the term ‘laser’. Credit: (AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives.

The origins of the development of the laser may be found in a paper by Albert Einstein (1879-1955) on stimulated emission of radiation in 1916 («Strahlungs-emission und -absorption nach der Quantentheorie», Emission and absorption of radiation in Quantum Theory). But it was an article published on 15 December 1958 by two physicists, Charles Townes (who died on 27 January of 2015 at the age of 99) and Arthur Schawlow (1921-1999) titled “Infrared and Optical Masers” that laid the theoretical bases enabling Maiman to build the first laser at the Hughes Research Laboratories (HRL) in Malibu, California in 1960. Maiman used as the gain medium a synthetic ruby crystal rod one centimeter long with mirrors on both ends and so created the first ever active optical resonator. It is probably not general knowledge that the Hughes Research Laboratories was a private research company founded in 1948 by Howard Hughes (1905-1976), eccentric multimillionaire, aviator, self-taught engineer, Hollywood producer and entrepreneur, played by Leonardo DiCaprio in the film “The Aviator” directed by Martin Scorsese in 2004.

The executives of the Hughes Research Laboratories gave Maiman a deadline of nine months, 50,000 dollars and an assistant to obtain the first laser emission. Maiman was going to use a movie projector lamp to optically excite the gain medium but it was his assistant, Irnee D’Haenes, who had the idea of illuminating the ruby crystal with a photographic flash.

Charles H. Townes (left) and Arthur Leonard Schwalow (right). Nobel Museum, Stockholm. Credit: A. Beléndez.

When he obtained the first laser emission, Maiman submitted a short article to the prestigious physics journal the Physical Review. However, it was rejected by the editors who said that the journal had a backlog of articles on masers –antecedent of the laser in the microwave region and so had decided not to accept any more articles on this topic since they did not merit prompt publication. Maiman then sent his article to the prestigious British journal, Nature, which is even more particular than the Physical Review. However it was accepted for publication and saw the light (excuse the pun) on 6 August 1960 in the section Letters to Nature under the title “Stimulated Optical Radiation in Ruby”, with Maiman as its sole author. This article which ran to barely 300 words and took up the space of just over a column may well be the shortest specialized article on such an important scientific development ever published. In a book published to celebrate the centenary of the journal Nature, Townes described Maiman’s article as “the most important per word of any of the wonderful papers” that this prestigious journal had published in its hundred years of existence. After Maiman’s article was officially accepted by Nature, the Hughes laboratories announced that the first working laser had been built in their company and called a press conference in Manhattan on 7 July 1960.

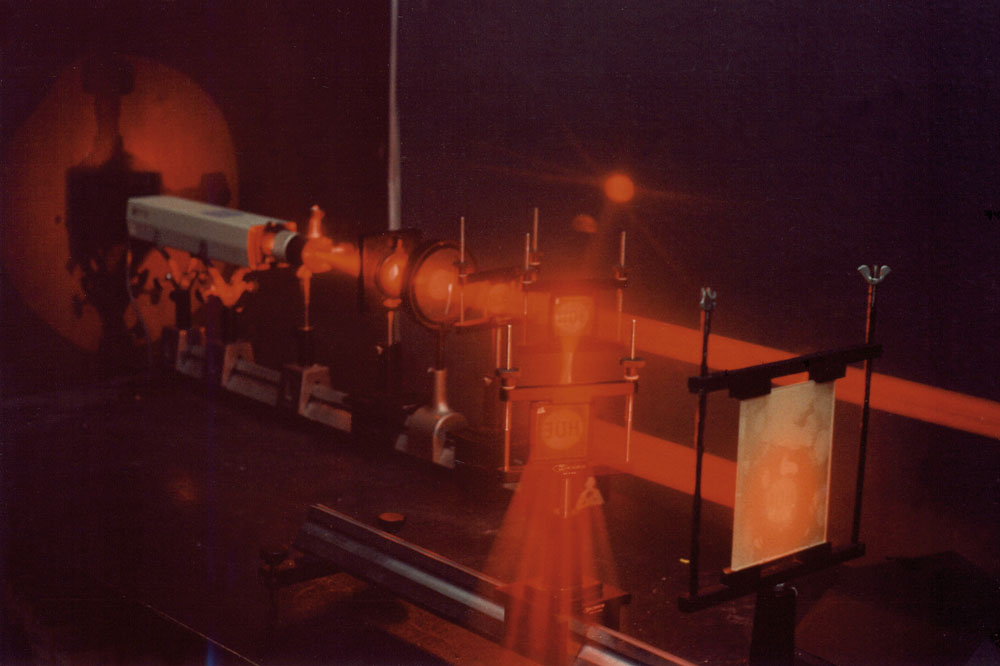

In a very short time the laser stopped being a simple curiosity and became an almost unending source of new scientific advances and technological developments of great significance. In fact the first commercial laser came on the market barely a year later in 1961. In the same year the first He-Ne lasers, probably the most well known and widely used lasers ever since, were commercialized. In these early years between 1960 and 1970 none of the researchers working on developing the laser –the majority in laboratories of private companies such as those of Hughes, IBM, General Electric or Bell- could have imagined to what extent lasers would transform not only science and technology but also our daily life over the subsequent 60 years.

On May 16, 2020, we celebrate the 60th Anniversary of Maiman’s monumental accomplishment in conjunction with the International Day of Light.

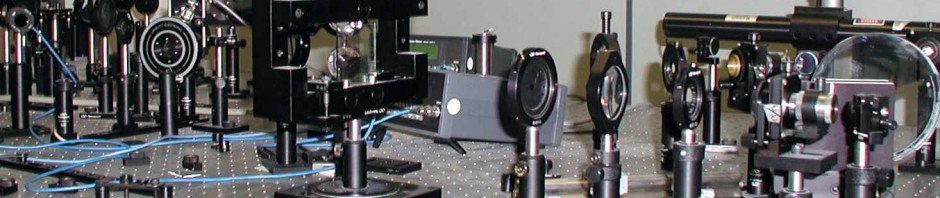

He-Ne laser illuminating an optical set-up formed by two holographic lenses in the Optics laboratory at the University of Alicante. The University of Alicante was one of the pioneer universities in Spain in the application of laser to research. / Augusto Beléndez, Variable holographic filter (1988).

“55th anniversary of the laser’s invention”: Published in IYL2015 BLOG (May 27th, 2015)