febrero 2026 M T W T F S S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 -

Entradas recientes

Etiquetas

- Ampliación de Física

- Anécdotas

- Applets

- Aprendizaje

- Asignatura

- Año de la Luz

- Biografía

- Ciencias

- Conferencias

- Dinámica

- Divulgación

- Docencia

- Día Internacional de la Luz

- Educación

- Einstein

- Electromagnetismo

- Enseñanza

- Entrevistas

- EPS

- Experiencias

- Experimentos

- Física

- Grado en Ingeniería Robótica

- Historia de la Física

- Innovación

- Investigación

- Laboratorio

- Maxwell

- Mecánica

- Mujeres en ciencia

- Noticias

- Ondas

- Optica

- Oscilaciones

- Premios Nobel

- Prensa

- Prácticas

- Radio

- Sociedad

- Sonido e Imagen

- Tecnología

- Telecomunicaciones

- TIC

- Universidad

- Vídeos

Meta

Mi editorial en el último número de 2018 de la Revista Española de Física

Posted in Divulgación

Tagged Divulgación, Física, Noticias, Prensa

Comments Off on Mi editorial en el último número de 2018 de la Revista Española de Física

Magnetismo: Los orígenes

Primeros descubrimientos

Como sucede con la electricidad, el fenómeno del magnetismo era conocido desde la antigua Grecia y también su nombre es de origen griego. La palabra magnetismo viene de la palabra “magnes”, imán en griego, que a su vez viene de Magnesia (Magnesia del Meandro), región del Asia Menor en la que se encuentran yacimientos del mineral magnetita (piedra imán), que tiene la propiedad de atraer objetos de hierro así como conferir al hierro sus propiedades magnéticas. Se observó que el efecto de atraer pequeños trocitos de hierro era más pronunciado en ciertas zonas del imán denominadas polos magnéticos.

Tales de Mileto (aprox. 624-546 a.C.) es considerado como uno de los primeros que asoció los fenómenos eléctricos y magnéticos. Tales conoció los efectos de la magnetita y pensó que si el ámbar al ser frotado era capaz de atraer pequeños objetos era porque se transformaba en magnético por el efecto del frotamiento. Sin embargo se dio cuenta que por mucho que frotara el ámbar, éste era incapaz de atraer pequeños trocitos o limaduras de hierro, que sí eran atraídos por la magnetiza, sin necesidad de ser frotada. De este modo, electricidad y magnetismo quedaron independientes e incomunicados durante más de dos mil años, justo hasta que Oersted descubriera en 1820 que una corriente eléctrica es capaz de desviar la aguja de una brújula.

Los polos magnéticos y la brújula

La utilización de una aguja imantada como brújula en navegación se remonta a la Edad Media aunque el conocimiento de las propiedades de la brújula ya era conocido por los chinos varios siglos antes y llevado a occidente por los árabes. En China, la primera referencia al fenómeno del magnetismo se encuentra en un manuscrito del siglo IV a.C. que lleva por título Libro del amo del valle del diablo y en el que señala que “la magnetita atrae al hierro hacia sí o es atraída por este”. La primera mención sobre la atracción de una aguja imantada aparece en un trabajo realizado entre los años 20 y 100 d.C.: “La magnetita atrae a la aguja”. El científico Shen Kua (1031-1095) escribió sobre la brújula de aguja magnética (o aguja de marear, como se llamaba en aquella época) y mejoró la precisión en la navegación empleando el concepto astronómico del norte absoluto. Hacia el siglo XII los chinos ya habían desarrollado la técnica lo suficiente como para utilizar la brújula para mejorar la navegación. Los chinos transmitieron sus conocimientos sobre la brújula a hindúes y árabes y fueron estos últimos los que la trajeron a Europa.

Alexander Neckam (1157-1217) fue el primer europeo en conseguir desarrollar la técnica de usar la brújula en navegación en 1187. Si una varilla imantada se suspende libremente en un punto de la superficie de la Tierra, la varilla se orienta en la dirección Norte-Sur. Este hecho permitió distinguir los extremos de la varilla o polos magnéticos norte (N) y sur (S) y concluir que la propia Tierra se comporta como un gran imán. Se observó, asimismo, que la fuerza entre polos del mismo nombre es repulsiva, mientras que la fuerza entre polos de distinto nombre es atractiva. A diferencia de lo que sucede con las cargas eléctricas los polos magnéticos siempre se presentan de dos en dos. No es posible tener un polo norte o un polo sur aislados y si se parte un imán para intentar separar sus polos, se obtienen dos imanes, cada uno de ellos con una pareja de polos norte y sur de igual intensidad. De estos experimentos se puede concluir que no existen monopolos magnéticos libres o, al menos hasta el momento, no han sido encontrados.

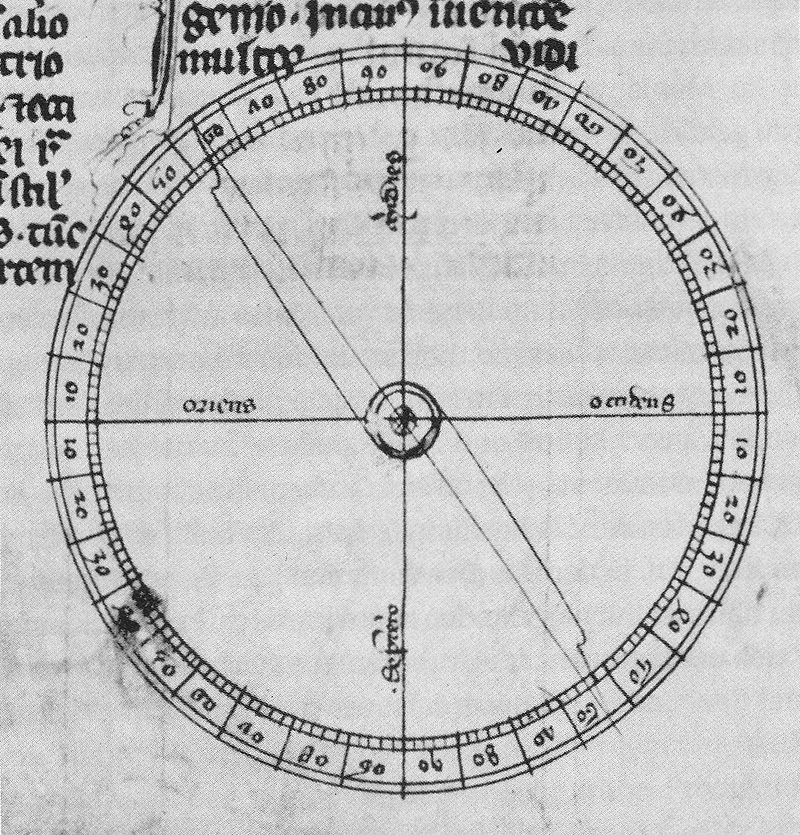

En 1269, Pierre Pelèrin de Maricourt, estudioso francés del siglo XIII, ingeniero militar al servicio de Carlos de Anjou y compañero de San Luis en la primera cruzada. En sus estudios presenta la primera descripción detallada de la brújula como instrumento de navegación. Descubrió que si una aguja imantada se deja libremente en distintas posiciones sobre un imán natural esférico, se orienta a lo largo de líneas que, rodeando el imán, pasan por puntos situados en extremos opuestos a la esfera. Estos puntos fueron llamados polos del imán. También observó que los polos iguales de dos imanes se repelen entre sí y los polos distintos se atraen mutuamente. Durante el sitio de Lucerna en Italia por Carlos de Anjou en agosto de 1269, Maricourt escribe su carta sobre el magnetismo, la Epistola ad Sigerum de Foucaucourt militem de magnete, conocida también como Epistola de magnete, que supone el primer tratado científico sobre las propiedades del los imanes.

Aguja rotatoria de una brújula en una copia de la ‘Epistola de magnete’ de Pierre de Maricourt (1269). Créditos: Wikipedia.

‘De Magnete’ y el magnetismo terrestre

William Gilbert (1544-1603), contemporáneo de Kepler y Galileo, llevó a cabo cuidadosos estudios de las interacciones magnéticas y publicó en 1600 sus resultados en un libro, “De magnete, magneticisque corporibus, et de magno magnete tellure” (Sobre los imanes, los cuerpos magnéticos y el gran imán terrestre), más conocido como De magnete, la primera descripción exhaustiva del magnetismo así como la primera gran obra de la física experimental. En la primera frase del prólogo Gilbert ya deja clara cual es su forma de proceder:

“En el descubrimiento de cosas secretas y en la investigación de las causas ocultas, los experimentos seguros proporcionan y demuestran sólidos argumentos en comparación con probables conjeturas y las opiniones de los especuladores filosóficos de tipo común.”

Una parte importante de la ciencia europea tiene sus raíces en las teoría iniciales de Gilbert y su afición por los experimentos. Gilbert estudió medicina y llegó a ser un médico de prestigio y en el año 1600 fue nombrado médico personal de la reina Isabel I de Inglaterra, aunque no debió ser muy bueno en ese cometido pues la reina falleció casi inmediatamente. El único legado personal que dejó la reina antes de morir fue una suma de dinero para William Gilbert con la cual éste pudo continuar sus estudios sobre magnetismo. En sus estudios Gilbert concluyó que la Tierra puede considerarse como un imán gigante con sus polos situados cerca de los polos norte y sur geográficos. Este concepto sobrevivió a través de los siglos, y después de haber sido desarrollado matemáticamente por el gran matemático Alemán Carl Gauss, es hoy un concepto fundamental en la teoría del magnetismo terrestre. También comprobó que si se divide un imán en dos partes, se obtendrá la formación de dos nuevos polos, “es imposible obtener un polo magnético aislado”, escribió.

‘De magnete’ y William Gilbert (1544-1603). Créditos: Wikipedia.

El magnetismo era uno de los ejemplos preferidos de los magos para probar la existencia de cualidades ocultas. Gilbert llegó a comparar los efectos de los imanes con los del alma, mientras que para René Descartes (1596-1650), sus Principia philosophiae (Los principios de filosofía), señala que el magnetismo era un torrente de corpúsculos que salían del cuerpo magnético y que tenían forma de tornillos de rosca derecha o izquierda, como un sacacorchos, por lo que dependiendo de la forma harían que los objetos a los que se acercaran se movieran hacia el imán o se alejaran del mismo. De este modo, Descartes explicó el magnetismo recurriendo a un flujo de partículas que saldrían de un polo del imán y entrarían en el otro.

En el siglo XVIII, por analogía con la electricidad, se supuso la existencia de dos fluidos magnéticos. Charles-Augustin Coulomb (1736-1806) estudió las fuerzas entre polos magnéticos y propuso la ecuación de la fuerza entre polos magnéticos semejante a la fuerza electrostática entre cargas eléctricas y la fuerza gravitatoria entre masas gravitatorias: La fuerza entre dos polos magnéticos varía de forma inversamente proporcional al cuadrado de la distancia entre los polos y de forma directa con la intensidad de los polos (medida por la fuerza que ejercen sobre un polo de valor determinado). La ley que rige las fuerzas de atracción y repulsión entre las cargas eléctricas y los polos magnéticos fue publicada en 1785 en un trabajo titulado Segunda memoria sobre la electricidad y el magnetismo. Como había hecho Gilbert casi doscientos años antes y Tales de Mileto dos mil años antes, Coulomb consideró que los fenómenos eléctricos y magnéticos eran diferentes, puesto que, a pesar de la estrecha analogía que parecía existir entre ellos, los experimentos indicaban que los polos magnéticos y las cargas eléctricas (entonces sólo en reposo) no interactuaban entre sí.

Gauss y los Observatorios Magnéticos

Una de las figuras claves en el desarrollo del magnetismo (y en el de otros muchos campos de la ciencia) es Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1855) que estableció el primer Observatorio Magnético en Gotinga e inició en él observaciones continuas sobre el magnetismo terrestre y desarrolló el primer magnetómetro. En 1832 publicó un artículo sobre la medición del campo magnético de la Tierra y describió un nuevo instrumento que consistía en un imán de barra permanente suspendido horizontalmente de una fibra de oro. La diferencia en las oscilaciones cuando la barra era magnetizada y cuando era desmagnetizada permitió a Gauss calcular un valor absoluto para la fuerza del campo magnético de la Tierra. La ley de Gauss del magnetismo, llamada así precisamente por Carl Gauss, es una de las ecuaciones fundamentales del campo electromagnético (ecuaciones de Maxwell) y una manera formal de afirmar que no existen polos magnéticos aislados (por ejemplo, un imán son polo norte o sur), es decir, monopolos magnéticos.

Wilhelm Eduard Weber (1804-1892), amigo y colaborador de Gauss, fue profesor en las Universidades de Leipzig y Gotinga, y sucedió a Gauss al frente del Observatorio Magnético de Gotinga. Weber propuso que las partículas de un cuerpo son intrínsecamente magnéticas, pero que sólo en ciertos materiales se mantienen todas ellas alineadas. Junto con su amigo Gauss inventó en 1833 un nuevo tipo de telégrafo conocido como telégrafo de Gauss-Weber.

Uno de las contribuciones más importantes de Weber fue el “Atlas Des Erdmagnetismus: Nach Den Elementen Der Theorie Entworfen” (Atlas de Geomagnetismo), confeccionado en colaboración con Gauss. Este Atlas está compuesto por una serie de mapas magnéticos de la Tierra que en su día suscitaron el interés de las principales potencias del momento lo que les llevó a fundar “observatorios magnéticos”. En el año 1864, y también en colaboración con Gauss, publica Medidas Proporcionales Electromagnéticas, texto que contiene un sistema de medidas absolutas para corrientes eléctricas y que sentó las bases de las medidas quede usan hoy en día. En 1856, junto con Rudolf Kohlrausch (1809-1858), ambos demostraron que el cociente de las unidades electrostáticas y las electromagnéticas daba lugar a un número que coincidía con el valor de la velocidad de la luz conocido por aquel entonces. Este hallazgo ayudó a Maxwell a conjeturar que la luz es una onda electromagnética. También, en un artículo publicado en 1856 por Kohlrausch y Weber, fueron los primeros en utilizar la letra “c” para designar a la velocidad de la luz.

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

Peter J. BOWLER e Iwan Rhys MORUS (2007), Panorama general de la ciencia moderna (Editorial Crítica, Barcelona).

Clifford A. PICKOVER, El Libro de la Física (Ilus Books, S.L. Madrid, 2011)

George GAMOW, Biografía de la Física (Alianza Editorial. Madrid, 1980).

Javier ORDÓÑEZ, Víctor NAVARRO y José Manuel SÁNCHEZ RON, Historia de la ciencia (Espasa-Calpe. Madrid, 2007).

Mª Carmen PÉREZ DE LANDAZÁBAL y Paloma VARELA NIETO, Orígenes del electromagnetismo. Oersted y Ampère (Nívola libros y ediciones. Madrid, 2003).

Agustín UDÍAS VALLINA, Historia de la Física. De Arquímedes a Einstein (Síntesis. Madrid, 2004).

Augusto BELÉNDEZ VÁZQUEZ, “La unificación de luz, electricidad y magnetismo: la “síntesis electromagnética” de Maxwell”. Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física. Vol. 30, No. 2 (Jun. 2008). pp. 2601-1/2601-20

Magnetismo, Wikipedia (consultado 28/04/2017).

Peter Peregrinus de Maricourt, Wikipedia (consultado 28/04/2017).

William Gilbert, Wikipedia (consultado 28/04/2017).

Posted in Divulgación, Historia de la Física

Tagged Biografía, Divulgación, Electromagnetismo, Historia de la Física

Comments Off on Magnetismo: Los orígenes

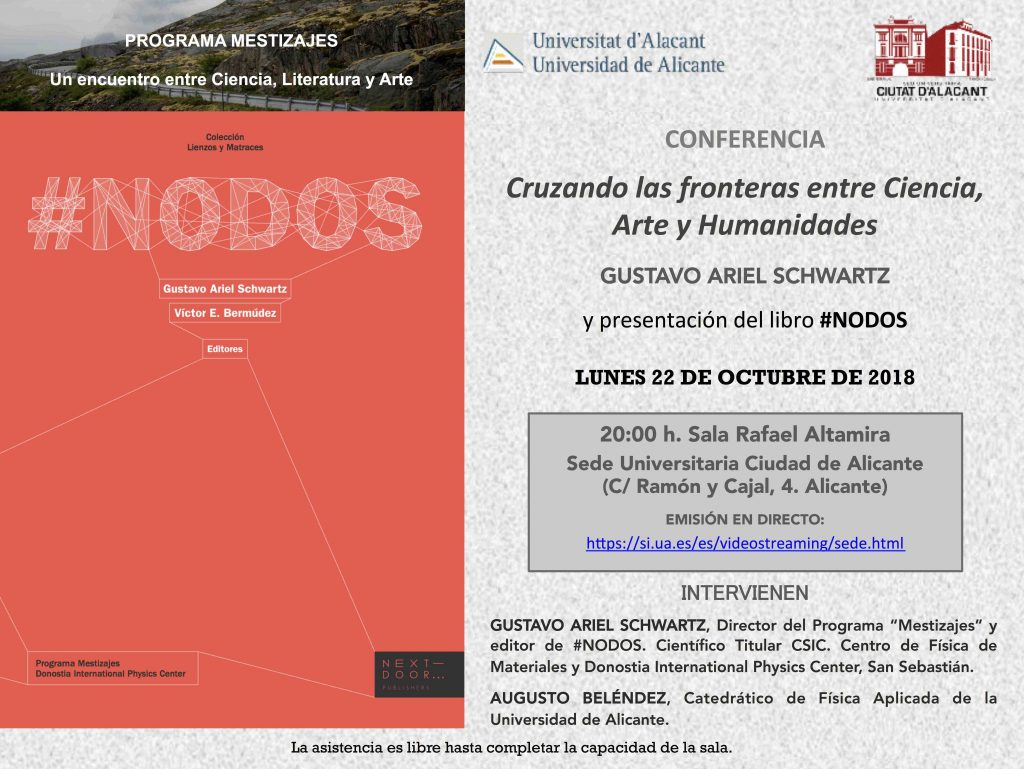

Presentación de la conferencia “Cruzando las fronteras entre Arte, Ciencia y Humanidades” y del libro #NODOS

El lunes 22 de octubre tuvo lugar en la Sede de Alicante de la Universidad de Alicante la presentación del libro #NODOS. En el acto intervino Gustavo Ariel Schwartz, Director del Programa Mestizajes y coeditor del libro #NODOS, quien además impartió la conferencia “Cruzando las fronteras entre Arte, ciencia y Humanidades”; así como Augusto Beléndez, Catedrático de Física Aplicada e investigador del GHPO del IUFACyT de la Universidad de Alicante.

El 7 de mayo de 1959 en la Universidad de Cambridge, más concretamente en la Casa del Senado -un edificio barroco en el que durante el siglo XIX y principios del XX se realizaban los exámenes del Tripos Matemático-, el químico-físico y novelista británico Charles Percy Snow pronunciaba la conferencia “Las dos culturas y la revolución científica”, conferencia en la que ponía de manifiesto la brecha existente entre el mundo de las ciencias y el mundo de las humanidades -dos galaxias incomunicadas que se contemplan con hostilidad y desagrado- y señalaba que además del empobrecimiento que esa mutua ignorancia lleva consigo, la falta de interdisciplinariedad entre ambos mundos es uno de los principales inconvenientes para la resolución de los problemas mundiales.

Hay un momento en el que a todos los adolescentes se les hace elegir entre ciencias y letras, elección que les marcará para toda su vida. Como si se tratara de un una especie de “iniciación tribal” de las sociedades occidentales, al hacer esta elección nos convertimos en alguien de ciencias o en alguien de letras hasta el final de nuestros días.

Es precisamente esa zona de confort en la que tan cómodamente nos encontramos cada uno en nuestro mundo científico, artístico o literario, la que no nos deja mirar más allá. Sin embargo, como nuestro conferenciante nos mostrará, ciencias y humanidades no son excluyentes; no existe un muro infranqueable entre ambas, más bien diríamos que sus fronteras son permeables y no sólo se pueden cruzar, sino que es necesario y beneficioso hacerlo.

La obra colectiva #NODOS es una aventura intelectual que explora las fronteras entre los diferentes ámbitos del conocimiento. Juan José Gómez Cadenas, físico de partículas elementales en el Laboratorio Subterráneo de Canfranc, novelista y uno de los colaboradores del libro, opina que #NODOS “no quiere ser un libro de ciencia, ni de arte, ni de literatura o humanidades, sino todo lo contrario o todo eso a la vez”. El físico teórico, historiador de la ciencia y académico de la lengua, José Manuel Sánchez Ron, en el prólogo de #NODOS señala que se trata de “una obra colectiva en la que la temática científica y la originalidad de sus planteamientos se hermanan con la buena literatura, esa que te captura por su estilo y te sorprende por sus contenidos”.

Para terminar mi intervención, y antes de ceder la palabra a nuestro conferenciante, sólo me queda hacer una breve semblanza del mismo.

Gustavo Ariel Schwartz se define asimismo como físico, escritor y mestizante. Se doctoró en física en la Universidad de Buenos Aires en 2001 y realizó estancias de investigación en Estados Unidos, Suecia y España. En la actualidad es científico titular del CSIC y desarrolla su actividad investigadora en el Centro de Física de Materiales de San Sebastián y ha publicado más de medio centenar de artículos científicos.

Es además fundador y director del Programa Mestizajes, en el Donostia International Physics Center, cuyo propósito consiste en explorar y transitar las fronteras entre Arte, Ciencia y Humanidades. En el marco de este programa, ha organizado en 2011, 2014 y 2017 tres Encuentros Internacionales sobre Literatura y Ciencia y ha puesto en marcha en 2012 el Programa Escritores en Residencia. Ha escrito, junto con Luisa Etxenike, la obra de teatro La entrevista que se estrenó en San Sebastián en Octubre de 2013 y en 2016 ha coordinado el proyecto Realidad Conexa, una colección de 8 cápsulas audiovisuales sobre la intuición y la razón.

Recientemente acaba de coeditar junto con Víctor Bermúdez la obra colectiva #Nodos, de la que también nos hablará aquí esta noche y en la que cerca de un centenar de científicos, escritores, artistas y pensadores de todo el mundo exploran las posibilidades del conocimiento transdisciplinar.

En la actualidad Gustavo Ariel Schwartz combina su labor de investigación científica con la dirección del Programa Mestizajes y la escritura de ensayos y ficciones que exploran las relaciones entre arte, ciencia y humanidades. Además de la obra colectiva #Nodos, ha publicado el libro de relatos El otro lado y la obra de teatro La entrevista, y mantiene el blog Arte, Literatura y Ciencia.

Posted in Divulgación

Tagged Ciencias, Conferencias, Divulgación, Historia de la Física

Comments Off on Presentación de la conferencia “Cruzando las fronteras entre Arte, Ciencia y Humanidades” y del libro #NODOS

Electricidad: Los orígenes

Primeros descubrimientos

El fenómeno de la electricidad era conocido desde la antigua Grecia y su nombre mismo es de origen griego. Electricidad proviene de la palabra griega electrón, es decir, “ámbar”, ya que era conocida la propiedad del ámbar de generar electricidad estática al ser frotado y atraer pequeños trocitos de tela o papel y el concepto de fuerza eléctrica tuvo su origen en experimentos muy sencillos como la frotación de dos cuerpos entre sí. Cuando se frota una varilla de vidrio o de ámbar con un trapo o una piel, aquéllas atraen pequeños trocitos de papel. Si se frota una barra de ámbar con un trozo de piel y se suspende de un hilo y se le aproxima una segunda barra de ámbar, frotada también con una piel, se observa que ambas barras se repelen. Lo mismo sucede si las dos barras son de vidrio pero frotadas con un trozo de seda. Sin embargo, si se aproxima una barra de ámbar frotada con una piel a una barra de vidrio frotada con un paño de seda, ambas suspendidas de sendos hilos, se observa que las barras se atraen entre sí. Esto permitió concluir que existían dos tipos de electricidad, la relacionada con el vidrio y la relacionada con el ámbar, de modo que los cuerpos con electricidades del mismo tipo se repelen mientras que con distinto tipo se atraen.

El fluido eléctrico

Los avances que se realizaron en la comprensión de los fenómenos relacionados con la electricidad desde la época de los griegos hasta los comienzos del siglo XIX no fueron muchos. Stephen Gray (1670-1736), tintorero de profesión, experimentador aficionado y colaborador de la Royal Society, descubrió que la electricidad se podía transmitir por un hilo metálico (a una distancia de unos 200 metros) y distinguió entre conductores y aislantes. Como en el caso del calor, la electricidad se concebía como un fluido que podía pasar de unos cuerpos a otros y, de hecho, aún hoy se habla de “fluido eléctrico”.

Experimento de Stephen Gray sobre la conducción de la electricidad.

Charles F. Dufay (1698-1739), químico y administrador del Jardín del Rey, comprendió las distintas propiedades de la electricidad de distinto signo y supuso que existían dos clases de electricidad: la producida frotando sustancias vítreas como el cristal o la mica, y la producida por el ámbar frotado, el lacre, la vulcanita y otras sustancias resinosas. Asignó a estas dos clases de electricidad unos fluidos eléctricos, uno denominado “vítreo” y el otro conocido como “resinoso”. Se suponía que los cuerpos eléctricamente neutros contenían cantidades equilibradas de ambos fluidos eléctricos, mientras que los cuerpos cargados eléctricamente tenían un exceso de electricidad resinosa o vítrea. En 1734 Dufay estableció que “la característica de ambas electricidades es que un cuerpo cargado con electricidad vítrea repele a todos los demás cargados con la misma electricidad y, por el contrario, atrae a los que poseen electricidad resinosa”.

La botella de Leyden

Por aquella época la electricidad se almacenaba en un dispositivo denominado botella de Leyden desarrollada por Pieter van Musschenbroek (1692-1761), profesor de matemáticas de la ciudad de Leyden (Holanda), a partir de un diseño realizado por Ewald Jurgen von Kleist (1700-1748) en 1745 formado por una botella de cristal con agua sellada con un corcho a través del cual se introducía un clavo hasta tocar el agua. Para cargar eléctricamente la botella se acercaba la cabeza del clavo a la máquina de fricción. Cuando la botella estaba cargada, si se acercaba a la cabeza del clavo un cuerpo no electrificado saltaba una fuerte chispa entre ambos. Musschenbroek recubrió el interior y el exterior de la botella hasta la mitad con panes de plata, de este modo el cristal de la botella hace el papel del aislante o dieléctrico del condensador. Si el pan exterior está conectado a tierra y el interior con un cuerpo electrizado, o viceversa, la electricidad (sea vítrea o resinosa) trata de escapar al suelo pero es detenida por la capa de cristal. Este dispositivo permitía acumular grandes cantidades de electricidad y se podían extraer chispas impresionantes conectando el interior y el exterior de la botella con un alambre. La primitiva botella de Leyden se ha convertido hoy en varios tipos de condensadores.

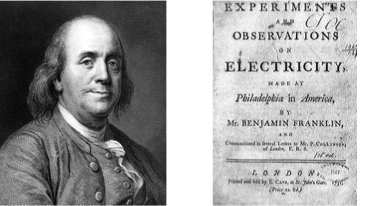

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), que comenzó a interesarse por la física a la edad de cuarenta años, concluyó que sólo existe un tipo de fluido eléctrico (la electricidad vítrea), en vez de dos como se admitía hasta entonces, y dos tipos de estados de electrización, una como la del vidrio y otra como la del ámbar, y llamó a la primera positiva y a la segunda negativa. De este modo, si un cuerpo tiene exceso de fluido eléctrico aparece con electricidad positiva (vítrea), y si tiene defecto la tiene negativa (resinosa). Cuando dos cuerpos, uno de los cuales tiene un exceso y el otro una deficiencia de fluido eléctrico, se juntan, la corriente eléctrica debe fluir desde el primer cuerpo, donde está en exceso, al segundo, donde falta. En 1754 identificó el rayo como una descarga eléctrica después de enviar cometas a las nubes tormentosas para recoger electricidad de ellas y desde entonces se le conoce como el padre del pararrayos. La cuerda húmeda que sostenía la cometa servía como un perfecto conductor de la electricidad y con ella podían cargarse botellas de Leyden y obtener después chispas de ellas. Sus experimentos con el pararrayos y sus ideas políticas, opuestas a las monarquías absolutas, motivaron que en un busto suyo se escribiera que había “arrancado el rayo del cielo y el cetro del tirano”.

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790).

Henry Cavendish (1731-1810), hombre extremadamente rico y extremadamente tímido y un personaje ciertamente solitario, fue uno de los primeros en utilizar el concepto de carga eléctrica. Hizo muchos experimentos y descubrimientos entre 1760 y 1800 como la medida de la capacidad de un condensador o el concepto de resistencia y desde luego fue uno de los científicos experimentales más grandes que han existido jamás. Sin embargo, sólo publicó dos artículos sobre electricidad y dejó veinte paquetes de manuscritos que quedaron en manos de sus parientes y no fueron conocidos hasta que, más de medio siglo después de la muerte de Cavendish, James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879), por entonces director del Laboratorio Cavendish de la Universidad de Cambridge, los puso en orden y los publicó en 1879.

La ley de Coulomb, el potencial y las máquinas electrostáticas

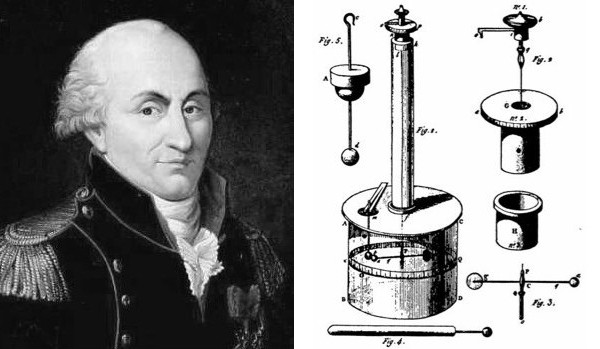

La ley que rige las fuerzas de atracción y repulsión entre cargas eléctricas fue descubierta y formulada en 1785 por Charles Augustin Coulomb (1736-1806), ingeniero militar francés que trabajó para Napoleón. trabajó para Napoleón y realizó importantes contribuciones en el campo de la elasticidad y la resistencia de materiales. En Física es conocido por la ley de Coulomb, aunque en el campo de la electrostática estudió las propiedades eléctricas de los conductores y demostró que si un conductor en equilibrio electrostático está cargado, su carga está en su superficie. En el año 1777 diseñó una balanza de torsión de gran sensibilidad formada por una varilla ligera que está suspendida de un largo y delgado hilo con dos esferas equilibradas a cada extremo. Con ayuda de esta balanza estableció de forma cuantitativa ocho años después la ley del inverso del cuadrado de la distancia para la interacción entre cargas eléctricas puntuales, conocida como ley de Coulomb. Según esta ley, la fuerza entre dos cargas puntuales es proporcional al producto de sus cargas e inversamente proporcional al cuadrado de la distancia que las separa. Esta fuerza es atractiva si las cargas son de distinto signo y repulsiva si el signo de las dos cargas es el mismo.

Charles Augustin Coulomb (1736-1806) y esquema de su balanza de torsión.

Siméon Denis Poisson (1781-1840), alumno de la Escuela Politécnica de París donde tuvo de profesores a Laplace y Lagrange y donde él mismo fue más tarde profesor, fue el primero en aplicar a la electricidad las ideas de Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749-1827) sobre el potencial gravitatorio. Introdujo el concepto de “potencial eléctrico” y en 1811 lo aplicó a la distribución de electricidad sobre una superficie en su obra “Memoria sobre la distribución de la electricidad sobre la superficie de los cuerpos conductores”. Poisson siguió pensando en términos de dos fluidos eléctricos aunque realmente estaba más interesado en la formalización matemática de las fuerzas entre cuerpos electrificados que la explicación física de los dos fluidos.

A pesar de los avances realizados en la comprensión de los fenómenos eléctricos, durante todo el siglo XVIII la única fuente de electricidad eran los generadores electrostáticos de rotación, tales como las construidas por Otto von Guericke (1602-1686), que producían electricidad estática por fricción y sólo eran capaces de suministrar descargas transitorias, lo que dificultaba el avance del estudio de la electricidad. Por esta razón, los primeros generadores electrostáticos son llamados máquinas de fricción al emplear la fricción como base en el proceso de generación. Era necesario, sin embargo, descubrir la forma de obtener un suministro estable y continuo de electricidad, es decir, de producir corriente eléctrica.

El galvanismo y la pila eléctrica

El precursor del descubrimiento de la corriente eléctrica continua fue el médico italiano Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) que estudió el efecto de la electricidad sobre los animales, siendo famosos sus experimentos con ancas de ranas realizados con máquinas eléctricas y botellas de Leyden. Galvani realizó un experimento, fechado el 20 de septiembre de 1786 en el diario de su laboratorio, en el cual empleaba una horquilla con un diente de cobre y otro de hierro con los cuales tocaba el nervio y el músculo del anca de una rana, la cual se contraía rápidamente a cada toque.

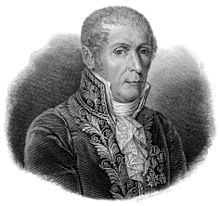

Sin embargo, fue el también italiano Alessandro Volta (1745-1827) quien interpretó que los dos metales juntos (hierro y cobre) de los experimentos de Galvani producían la corriente eléctrica después de sumergirlos en una solución salina y las ancas de rana sólo reaccionaban ante ella. Volta llamó “galvanismo” a este fenómeno y hacia 1800 fue capaz de producir una corriente eléctrica con una pila de discos de estaño o zinc y cobre o plata alternados y separados por otros de cartón impregnados de una solución de sal. De esta pila de disco es de donde proviene el nombre de “pila” voltaica que se ha generalizado para designar a las baterías eléctricas de este tipo. Napoleón se interesó mucho por los descubrimientos de Volta y mandó construir una gran pila voltaica en la Escuela Politécnica de París.

Alessandro G. Volta (1745-1827).

Humphry Davy (1778-1829), científico de la Royal Institution de Londres, explicó en 1807 que el proceso generador de la electricidad lo constituyen los cambios químicos en la pila. Davy utilizó la pila de Volta para separar metales introduciendo los electrodos en disoluciones de sales, iniciando el proceso de electrolisis. Como anécdota señalar que ante la pregunta de cuál había sido su mayor descubrimiento, las respuesta de Davy fue “mi mayor descubrimiento ha sido Michael Faraday”. Precisamente Michael Faraday (1791-1867), trabajando con Davy, descubrió las leyes de la electrólisis.

Circuitos eléctricos

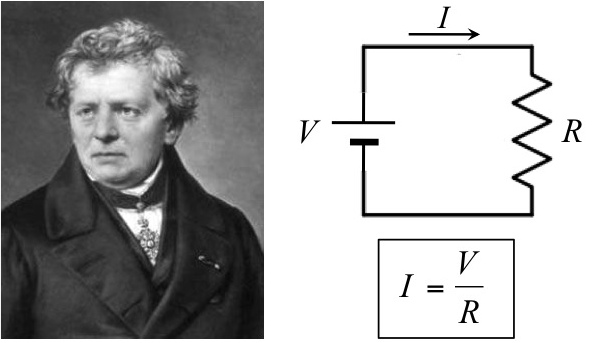

Georg Simon Ohm (1878-1854) aplicó al fenómeno de la electricidad por un alambre algunos descubrimientos hechos por Fourier sobre la propagación del calor, mediante una analogía entre la corriente eléctrica y la transmisión del calor. Obtuvo la relación entre diferencia de potencial, intensidad de corriente y resistencia conocida como ley de Ohm. Publicó sus resultados en un artículo titulado “el circuito galvánico investigado matemáticamente” y publicado en 1827. Sin embargo, su trabajo tuvo una mala acogida y hubo que esperar para que fuera reconocido hasta 1845, año en el que Gustav Kirchhoff (1824-1887), siendo estudiante en Könisberg, formuló las dos leyes de los circuitos que llevan su nombre: la ley de los nudos, relacionada con la conservación de la carga eléctrica, y la ley de las mallas, relacionada con la conservación de la energía.

Georg Simon Ohm (1878-1854).

BIBLIOGRAFÍA

Peter J. BOWLER e Iwan Rhys MORUS (2007), Panorama general de la ciencia moderna (Editorial Crítica, Barcelona).

José Antonio DÍAZ-HELLÍN (2001), El gran cambio de la Física. Faraday (Nívola libros y ediciones, Madrid).

George GAMOW (1980), Biografía de la Física (Alianza Editorial, Madrid).

Gerald HOLTON y Stephen G. BRUSH (1988), Introducción a los conceptos y teorías de las ciencias físicas (Editorial Reverté, Barcelona).

Javier ORDÓÑEZ, Víctor NAVARRO y José Manuel SÁNCHEZ RON (2007), Historia de la ciencia. Editorial Espasa-Calpe, Madrid.

Mª Carmen PÉREZ DE LANDAZÁBAL y Paloma VARELA NIETO (2003), Orígenes del electromagnetismo. Oersted y Ampère (Nívola libros y ediciones, Madrid).

Agustín UDÍAS VALLINA (2004), Historia de la Física. De Arquímedes a Einstein (Editorial Síntesis, Madrid).

Augusto BELÉNDEZ VÁZQUEZ (2008). “La unificación de luz, electricidad y magnetismo: la “síntesis electromagnética” de Maxwell”. Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física. Vol. 30, No. 2 (Jun. 2008). pp. 2601-1/2601-20

Posted in Divulgación, Historia de la Física

Tagged Biografía, Divulgación, Electromagnetismo, Historia de la Física

Comments Off on Electricidad: Los orígenes

Conferencia “Cruzando las fronteras entre Arte, Ciencia y Humanidades” por Gustavo Ariel Schwartz (Sede Ciudad de Alicante-UA, 22 de octubre a las 20 h)

El lunes 22 de octubre a las 20:00 h en la Sede Ciudad de Alicante de la Universidad de Alicante (Av. Ramón y Cajal nº 4, 03001 Alicante), y en el marco del Programa Mestizajes del DIPC, el Dr. Gustavo Ariel Schwartz impartirá la conferencia “Cruzando las fronteras entre Arte, Ciencia y Humanidades” junto con la presentación del libro #Nodos (Ciencia, Literatura, Arte y Humanidades).

PROGRAMA MESTIZAJES

El Programa Mestizajes, financiado por el Donostia International Physics Center (DIPC) con la colaboración del Centro de Física de Materiales (CFM) del CSIC, constituye un espacio alternativo para el encuentro de artistas, escritores, científicos y humanistas. Un lugar para el debate, para pensar diferente, para imaginar; un lugar para la búsqueda, para el encuentro y también para el desacuerdo; un lugar para la generación y la comunicación de nuevas formas de conocimiento. Mestizajes pretende abrir un camino que permita transitar la frontera entre arte, literatura y ciencia y crear allí un terreno fértil para la generación de nuevas ideas. La idea fundacional de Mestizajes es que se ha abierto una grieta en la muralla que separa arte, literatura y ciencia y que es posible transitar esa frontera e internarnos en un territorio emergente cargado de un enorme potencial humano e intelectual.

GUSTAVO ARIEL SCHWARTZ

La idea original del Programa Mestizajes y el director del mismo es Gustavo Ariel Schwartz. Nacido en Buenos Aires (Argentina) en 1966, el Dr. Ariel Schwartz estudió física en la Universidad de Buenos Aires donde se licenció en 1995 y se doctoró en 2001. Desde 2002 se dedica a investigar las relaciones entre ciencia y arte, las influencias recíprocas y las ideas comunes. En 2005 ganó su primer concurso literario con el cuento “La filtración”, que transcurre precisamente en esa frontera difusa entre racionalidad e irracionalidad, entre ciencia y arte. Desde 2008 es científico titular del CSIC y desarrolla su actividad investigadora en el Centro de Física de Materiales en San Sebastián. En 2010 fundó el Programa Mestizajes que desde entonces dirige.

#NODOS

Gustavo Ariel Scwartz es, junto con Víctor E. Bermúdez, coeditor del libro #Nodos, una obra colectiva en la que 89 científicos, escritores, artistas y humanistas reflexionan acerca de diversos temas que por su complejidad requieren necesariamente de un abordaje transdisciplinar. #Nodos, publicado por la editorial Next Door Publishers, ha sido escrito en el marco del Programa Mestizajes como resultado de una colaboración singular entre un científico y un humanista; pero es, sobre todo, una obra colectiva y global con una clara vocación transdisciplinar y un espíritu de integración más allá de las fronteras geográficas o disciplinares. La singularidad y el valor de #Nodos es resultado de la heterogeneidad y la excelencia de sus colaboradores.

Posted in Divulgación

Tagged Ciencias, Conferencias, Divulgación, Noticias

Comments Off on Conferencia “Cruzando las fronteras entre Arte, Ciencia y Humanidades” por Gustavo Ariel Schwartz (Sede Ciudad de Alicante-UA, 22 de octubre a las 20 h)